What is Amblyopia?

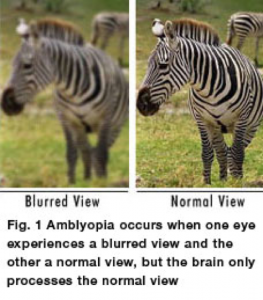

Amblyopia is decreased vision in one or both eyes, which occurs during the development of vision during infancy and childhood. In the past, slang for amblyopia was “lazy eye,” but that terminology is not preferred today because “lazy” behavior does not describe the child’s visual development with amblyopia. For example, Figure 1 shows how one eye has a blurred view (left photograph) in comparison to a clear, normal view (right photograph).

When a toddler or child has amblyopia, there may not be an obvious problem with the eye, especially when there is vision loss in one eye. Vision loss occurs because nerve pathways between the eye and the brain are not fully and properly stimulated. During amblyopia, the brain “incorporates” the blurry images from the amblyopic eye. As a result, the brain favors the better seeing, non-amblyopic eye, due to the decreased vision in the amblyopic eye.

Our vision develops during the first decade of life, but the most critical development for vision is the first five years of life. At birth, infants have very poor vision, however as they use their eyes, the vision improves because the brain’s vision centers are developing and are being stimulated. If infants are not able to use their eyes for various reasons, the brain’s vision centers do not develop fully and properly and a child’s vision is decreased despite a normal appearance of the eye’s structures.

Amblyopia is the leading cause of vision loss in children, affecting 2 to 3 out of every 100 children. I will focus on three main forms of amblyopia:

(1) refractive, (2) strabismic, and (3) deprivational. Multiple causative factors can co-exist, but I will describe each form of amblyopia in isolation

(1) Refractive Amblyopia

The most common cause of amblyopia is increased or asymmetric refractive error in one or both eyes. Refractive amblyopia happens when there is a large or unequal amount of refractive error (need for glasses from farsightedness or nearsightedness and/or astigmatism) between a child’s eyes.

The terms of farsightedness, nearsightedness and astigmatism refer to the ability of the eye to focus light on the retina. Farsightedness, or hyperopia, occurs when the distance from the front to the back of the eye is too short. Eyes that are farsighted tend to focus better at a distance but have more difficulty focusing on near objects. Nearsightedness, or myopia, occurs when the eye is too long from front to back. Eyes with nearsightedness tend to focus better on near objects. Eyes with astigmatism have difficulty focusing on far and near objects because of their irregular shape.

The brain “learns” how to see well from the eye that has less need for glasses and does not “learn” to see well from the eye that has a greater need for glasses. The child sees well with the better seeing eye.

Additionally, the amblyopic eye may not look any different from the normal seeing eye. Therefore, parents and pediatricians may not think there is a problem because the child’s eyes look normal. For these reasons, this kind of amblyopia in children may not be found until the child has a vision screening test. This kind of amblyopia can affect one or both eyes and can be best helped if the problem is found early.

(2) Strabismic Amblyopia

Strabismic amblyopia develops when the eyes are not straight or have an eye misalignment. One eye may turn inward (esotropia), turn outward (exotropia), upward (hypertropia) or downward (hypotropia). When there is strabismus or ocular misalignment, the brain begins to “ignore” the eye that is not fully aligned and the vision is subsequently decreased in the eye with strabismus and/or misalignment.

(3) Deprivational Amblyopia

Deprivational amblyopia develops when there is a central area blocking light which “deprives” a children’s eyes of vision. Typically, eye illnesses such as severe congenital ptosis (drooping eyelid), cataracts (lens opacity), cloudy corneas, glaucoma, macular retinal diseases cause this form of vision loss. If this form of amblyopia is not treated very early, these children do not see very well and can have very poor vision. Sometimes, this kind of amblyopia can affect both eyes.

Detecting Amblyopia

Early detection of amblyopia and subsequent treatment is always best.

The most common treatment of amblyopia is wearing glasses. If necessary, children with a significant refractive error (nearsightedness, farsightedness and/or astigmatism) can wear glasses when they are infants. Sometimes, patching the non-amblyopic eye is needed to help the vision in the eye with amblyopia. Moreover, children with illnesses such as significant cataracts, cloudy corneas, glaucoma, and significant ptosis are usually treated promptly, with surgery, in order to minimize amblyopia.

If a child’s amblyopia is detected later, it is still worthwhile to treat the amblyopia to improve vision. A recent National Institutes of Health (NIH) study with the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) confirmed that there is some visual improvement attained with amblyopia treatment up to 12 years old. However, clinical research demonstrated that improved amblyopia treatment success is achieved when treatment starts in children before 7 years old.

Vision screening is strongly recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus (AAPOS). Children are being screened initially within the first year of life and then subsequently, over the course of childhood at the pediatrician’s office. Pediatricians check newborns for a red reflex in each eye. Within the first few months of life, infants are checked for the ability to “fix and follow” in each eye. In the pediatric ophthalmologist’s office, children have a complete eye exam including pupil dilation and retinoscopy, to check for refractive error. The retinoscope instrumentis used to identify a refractive error that may need correction. When toddlers or school-age children can consistently identify shapes or letters either by matching or by reading, the visual acuity of each eye is recorded.

Main Amblyopia Treatments

(1) Glasses (spectacles)

One of the most important treatments of amblyopia is correcting the refractive error with consistent use of glasses (spectacles). Glasses usually improvesvisual acuity and depending on the age of the child and the significance of the refractive error, the vision improves with glasses. When a new pair of glasses are prescribed, it is typical for the pediatric ophthalmologist to evaluate your child again, wearing the glasses, to ensure that the frames are fitting his/her face and that there is an improvement in vision with the new glasses. Sometimes, glasses are needed to treat the amblyopia in only one eye (monocular). Other times, the amblyopia is in both eyes (bilateral). For monocular and bilateral amblyopia, wearing glasses will help treat amblyopia. Plastic frames are helpful in children, especially as these types of frames fit their faces well and are more durable with a child’s high level of activity.

(2) Patching (occlusion)

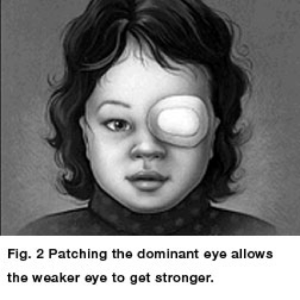

Patching is an effective way of treating amblyopia and often we use a soft patch to fit over the glasses or use an adhesive patch is worn over the stronger (non-amblyopic) eye. Occlusive patching of the better seeing (non-amblyopic) eye (see Figure 2) allows the amblyopic eye to improve. In Figure 2, the child’s left eye is being patched to help the vision of the right eye. We recognize that it is very challenging to make a young child wear a patch. It needs a lot of effort, persistence and encouragement from caregivers, family members and parents. The younger the child is, the faster patching works to improve the vision, therefore, we are persistent to treat amblyopia. When patching is initiated, the pediatric ophthalmologist will regularly evaluate how the patching is affecting the chid’s vision.Patching treatment forces the child to use the eye with amblyopia. Patching stimulates the vision and visual development in the weaker, amblyopic eye and helps parts of the brain involved in vision to develop more completely.

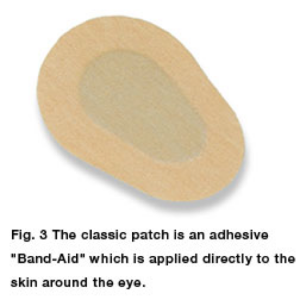

The classic patch is an adhesive “Band-Aid” which is applied directly to the periocular skin around the eye (see Figure 3). The adhesive patches are also available with different designs and colors and in different sizes for younger and older children. For children wearing glasses, a cloth patch is preferred and is placed over the spectacle of the non-amblyopic eye. Most pediatric ophthalmogists do not use “pirate” patches on elastic bands because they are especially prone to peeking and therefore, not as successful amblyopia treatment.

Previous clinical studies from PEDIG showed that patching the unaffected (non-amblyopic) eye of children with mild amblyopia for two hours daily worked as well as patching for six hours daily. Shorter patching time can lead to better compliance with treatment and improved quality of life for children with amblyopia. Most pediatric ophthalmologists will advise to patch the non-amblyopic eye while doing near activities such as reading, arts-and-crafts, drawing, and video games to stimulate the amblyopic eye to improve vision. Another clinical study with PEDIG showed that children with persistent moderate amblyopia over 6 years old may benefit from increased patching beyond two hours daily to daily patching extended to 6 hours. The pediatric ophthalmologist with work with the child’s parents for the appropriate amount of time for patching, depending upon your child’s level of amblyopia.

Also, if a child over the age of 8 years old with previously unknown amblyopia has a later diagnosis of amblyopia, it is still worthwhile to treat and patch the non-amblyopic eye. Clinical studies with PEDIG showed that an initial treatment for amblyopia in children and teens from ages 7 to 14 years old benefited from treatment for amblyopia. Therefore, diagnosis and treatment with the pediatric ophthalmologist is an important step for us to treat your child and teen’s amblyopia to promote the best possible visual outcome.

(3) Eye drops (penalization with Atropine 1% ophthalmic solution)

Instead of occlusive patching, sometimes the non-amblyopic eye can be be blurred or “penalized” with eyes drop treatment of Atropine 1% ophthalmic solution to help amblyopic eye improve in vision. Atropine eye drops are placed in the better seeing (non-amblyopic) eye and will temporally blur the vision in the eye. The eye drop treatment can work as an alternative to the occlusive patching. Clinical studies with PEDIG showed that in cases of mild to moderate amblyopia, the Atropine eye drop worked as well as occlusive patching. Once an Atropine eye drop treatment is initiated, the pediatric ophthalmologist will make sure that there are no side effects from the eye drop treatment, either ocular or systemic side effects.

If a school-age child notices that his/her better seeing eye is blurry with the Atropine eye drops, often glasses with magnification (bifocal) is provided to improve vision in the non-amblyopic eye with the Atropine eye drop treatment. The pediatric ophthalmologist works with a child’s parents/caregivers to help you select what treatment regimen is best for your child.

It should be noted that not all children benefit from Atropine eye drop treatment for amblyopia. Atropine 1% eye drops for amblyopia do not work as well when the non-amblyopic eye is nearsighted or when child’s amblyopia is severe. The pediatric ophthalmologist will work with each parent/caregiver to ensure the proper treatment is performed for your child’s amblyopia.

Credit for Figures 1,2,3: www.aapos.org: American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus.

Blog posted by Dr. Jennifer Galvin.

Dr. Galvin is a pediatric ophthalmologist. Pediatric ophthalmologists are medical and surgical doctors (Eye M.D.s) who specialize in the eye problems of children. In addition, pediatric ophthalmologist training includes specialization in ocular misalignment, strabismus and diplopia in adults. Dr. Jennifer Galvin completed her pediatric ophthalmology and adult strabismus fellowship training (2008-2009) at the University of Michigan/Kellogg Eye Center, under the mentorship of Dr. Monte Del Monte and Dr. Steven Archer.

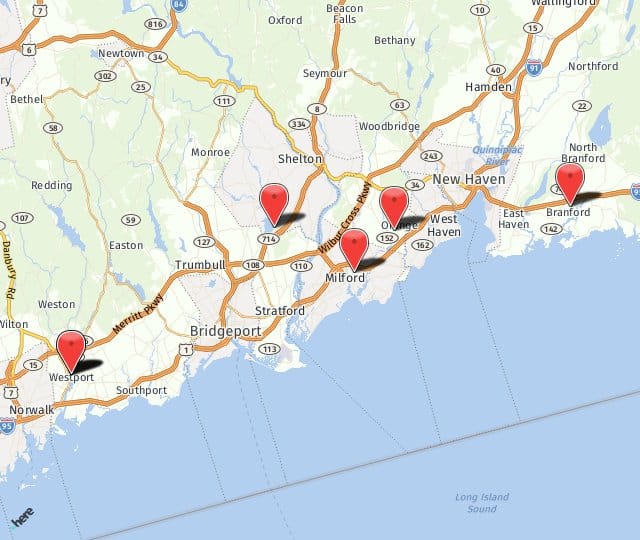

For more information on amblyopia or any of the services we offer, please contact us (203) 878-1236 at any of our 5 offices in Milford, Orange, Branford, Shelton, or Westport. We’re looking forward to hearing from you soon.